Conversation with a Renaissance Man, Pt. 1

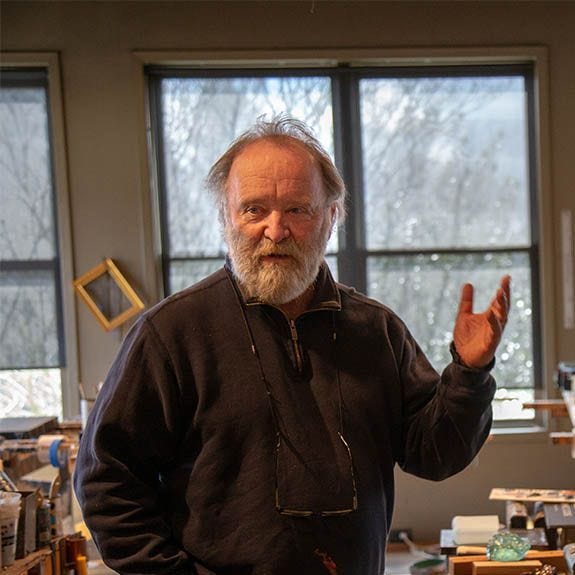

A record of my conversation with Seattle artist and self-taught cosmologist Dennis Evans about his life, thought and his 50-year retrospective show in Salem, Oregon.

Since I started writing for Oregon ArtsWatch in 2018, I’ve had occasion to cover a dozen exhibitions at the Willamette University-affiliated Hallie Ford Museum of Art in Salem, Oregon. It’s been a wonderful immersion into the world of visual art, which was so new to me then I found it intimidating. I still regard it as a new field of inquiry, and I can’t get enough of it.

ArtsWatch this week published my story about their latest show: Dennis Evans—Apocrypha, which is a 50-year retrospective of a remarkable man from Seattle, where he has been a working artist for his entire adult life. The show runs through Aug. 31 and if you live in these parts, I strongly urge you to carve out a few hours to see it and the museum’s other offerings.

A couple days after the opening reception for Evans, I returned to the Hallie Ford one weekday morning before they opened, and sat down with him in the museum’s Melvin Henderson-Rubio Gallery, now filled with stunning encaustic/mixed media work done in collaboration with his wife and nationally recognized glass artist Nancy Mee. We talked for an hour, and thanks to the wonders of AI, my device spit out a transcript of our conversation.

The numerous direct quotations in the ArtsWatch piece comprise maybe 150 words. To supplement that story and shed more light on the artist and the show, I’ve decided to publish here the transcript of our necessarily wide-ranging conversation—necessary because, as you will see, Evans is one of those rare souls who deserves the descriptor of a“Renaissance man.” His lifelong learning bridges many languages, philosophy, art, religion, history, literature, and the hard sciences—chemistry, math, physics, etc. He is refreshingly void of any pretension.

I realized before seeing the show or talking with Evans that this was going to be a very deep dive because I saw the exhibition’s book. It is itself an elegant work of art that packages journalism, photography and criticism by Matthew Kangas, a Seattle arts writer and curator who has basically played Boswell to Evans’ Johnson over the last half century. He’s followed the artist’s career since the mid-1970s. Throughout this conversation, we refer to material in this book and, in Part II, to the author. One more bit of context: Another name that comes up here is John Olbrantz, the long-time director of the museum.

Of course, this transcript has been heavily edited for clarity and length, but I think it reads well either as a stand-alone piece or as a supplement to the ArtsWatch story. At more than 5,000 words, I decided to break it into two parts. Today, Part I. Enjoy!

First, tell us a little about how this show came about.

The guy who designed my book, Phil Kovacevich, does a lot of publications for this museum. Phil lives in new York, but he went to the University of Washington, and so did John Olbrantz. We were all at UW in 1975. Phil designs books all over the place. I bet he does five to eight a year, he’s a serious book designer. I knew him a little, and when I started to do my book, I hired him to design it. He was really proud of it, and he talks to John a lot, and he told him, “I just did a book for Dennis Evans, you should really look at the book and consider his work.” John’s curated me in other shows at other museums, so he emailed me and said, “Do you want to have a show here in 2024?” I said “Yes, I do.” And he said, “It’s going to be a retrospective, and we’re going to use that book as the catalog.”

That’s fantastic.

So that’s how it happened.

I’m always fascinated by influences, so I’m just wondering to what extent your intellectual and artistic influences were a direct result of your formal education, as opposed to just you going off on your own down rabbit holes.

When I got into grad school, just by chance, I was given a graduate advisor, Jan van der Marck, who was a Dutch art historian and Christo’s project manager. He was running the Henry Gallery, which was like this gallery, but for the University of Washington. I was lucky, I was one of his two grad students. He educated me about a different art history than the traditional ones that they taught in European art history - the Fluxus artists, Dada. That totally directed my work. I thought, this is the kind of work I want to make.

The author of the book, Matthew Kangas, writes that at a certain point you became aware of the "remarkable similarities to French writers and creative figures of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.” What did you feel you had in common with them?

Just their free thinking. I got exposed to them through van der Marck, and it was the European approach to contemporary art that really changed me. As far as I was concerned, there were two tracks of art: One was the Matisse-Picasso, track and the other is the Marcel Duchamp/Andy Warhol conceptual track. That (latter) side of the track spoke to me.

The French writers who started deconstructing language really turned me on as well. Claude Levi-Strauss and Umberto Eco, semiologists working on language, taking language as a subject and exploring how meaning can be conveyed with letters and symbols, things like that.

Were you already a big reader?

I was. I was educated by Jesuits. Four years of Jesuit boys school in a little tiny town, so we had very scholarly approach. We read Latin and Greek, we read the classics in high school in Yakima, Washington.

They don’t do that anymore.

No, they don’t do that anymore.

I was at the lecture the other night, and before you started talking, there was an image projected on the wall of The Seeker card from the Tarot.

Yeah.

At other points in your life, given an opportunity to talk about your work and what you were doing, would you have used that card?

Yeah, that was probably a big part of me even in ‘73 ’74, ’75. When I got into art school, I was self-educating myself because the Jesuits taught me to always be curious. Early on I was exposed Carl Jung and his writings, the Bollingen Series of books from Princeton. I bought every one of them I could find and read every one of them. Western alchemy became a journey for me, spiritually and in my work, and that character was the character of the hero — Joseph Campbell’s hero, but in an alchemical robe. That was me: Seeker with ideas. I’ve never had great ambitions as an artist to become a Frank Stella or somebody in New York. I was curious about ideas, and that’s what motivated my work and pushed my work.

You began your talk by posing the question, “Where does art come from?” I thought I would just lob that back to you and ask: Where does that question come from? Why do people even ask that?

When I got my book and gave to it friends who had known me for a long time, many of them didn't know the whole story about me. Very few people knew about those performance pieces, and they said, “Where is this work coming from?” John also wanted me to talk about where my work came from, so I started thinking about that, and it was like, “God I don't know where this came from.” I can give you a bunch of constellations of influences, but to this day, I don't know where the impulse for artists to crawl into caves and make marks and all, where the hell that comes from. I don't have a clue.

And the fact that they did so at a time where presumably the only thing you would've been focused on was surviving! I mean, eating, shelter, protection from beasts. But given all that, they still crawled into caves and made these beautiful paintings.

Yeah. I taught kids for about 15 years in a very small private high school in Seattle. I taught art, obviously, and I would talk to them about that. What do you suppose made the desire of Homo sapiens to go do that when you had to think about getting food — just what you said, you know: Staying warm, staying alive, and then: Let’s go paint! It’s like, what the hell?

There’s a couple quotes in the book I wanted to throw back at you. You say that "the fabled mystical artistic tradition of the American Northwest had zero influence on my work. My primary influences were European art and artists.” It seems to me that people make a lot of the power of place and geography insofar as how it influences artists, regardless of whether it's painting or poetry or music. I’m curious as to why local art had zero influence. I mean, were you just not interested?

The big Northwest artists just didn't speak to me. We called them the fin and fur people. It was a mystical kind of thing, and their art just didn’t speak to me, it just left me dead. I’d rather go see a Joseph Beuys show than a Morris Graves show. Again, it was just the novelty and intellectual audacity of the Dada and Fluxus artists that stimulated the shit out of me. As a kid who had no real background in art at all, this was exciting stuff.

The cutting edge stuff.

Yeah. Canning your shit and then signing it and then putting that out as art. It was like, ‘God!’ Walter de Maria would drill a hole a thousand meters deep and put a bronze shaft down there and then put a plate over the top and call it Vertical Earth Kilometer. Just that attitude about making art stimulated me.

The other quote that jumped out at me was, you said, ‘The myths that drove my work for 40 years are now dead to me.”

The only thing I care about today is: Where did the universe come from? When the Big Bang happened, was there anything before that? And the thought of us — the hero, Homo sapiens — we are a speck floating in this immense universe. Those are the questions I live with now. So these old stories, which I loved and still love, but they became dead to me as driving forces in my creations.

And that was my next question … you told the story at the lecture, but if you could just repeat it here, about how you shifted to your current work. You mentioned hearing the story on the radio.

Often I can’t go to sleep right away, and I found that if I put in a little earbud and listen to the BBC at night, I fall asleep much faster. So about 4 o:clock in the morning, July 4, 2012, they have this breaking news on the BBC that physicists at CERN, Switzerland had just found evidence of a Higgs Boson. And it had been done a couple times, so they knew it was good evidence.

They’d repeated it.

Yeah, and I knew enough about physics to know that that was a big deal. That particle was missing in the standard model of particle physics.

I wondered if that was something you were already following.

A little bit. I have a very voracious appetite for ideas. I read broadly, so I knew about that. And I said, ‘Oh shit, this is it! They finished the puzzle!” And I grabbed Nancy’s leg, and she said, ‘What’s wrong, are you having a heart attack?’ I said, ‘No, but I just heard the work I’m going to do the rest of my life.’ And the next morning I just plowed into it. I had this background in science, so I relearned calculus, I started taking math classes online at Stanford, because math is the language of the universe. I just fell into that. Since 2012, I’ve read probably every book that’s come out about quantum physics.

Did you see that discovery as answering a question, or raising more?

Well, both, because as I started reading more about it I realized, this is an awesome question. And also, if the Higgs Boson — which is a field, really — existed at the Big Bang, it raises the question of what was the Big Bang? What caused that? I started reading cosmology. When people say, ‘Are you an artist now?’ I say ‘No, I’m a cosmologist and I make art about cosmology.’ This is what artists should be making art about, in my mind.

Cosmology is the field of study that attempts to understand the physical universe as a unified whole and to get at a ‘theory of everything.’ Do you see your art as a tool for getting those same questions, the scientific questions?

Yeah. I’ve produced a lot of paintings about dark matter, dark energy. They’re answers that artists would make. They’re not scientific answers. What’s interesting is that CERN has an arts program.

Do they?

Yes, a very robust one. And I was on my way there to apply for a residency. I had reservations in London for some event with my wife, and then we were going to Switzerland. And in the spring of that year, I saw Covid appearing, and it hit Seattle right away, big-time, and I said, ‘We’re not going.’

Oh, dammit!

Yeah! Right? So I’m going back. I mean, I’m definitely going to go back. I’ve learned more about the art that’s in those programs, and I’m way too traditional. The art that CERN is showing is people doing sound and all kinds of stuff, and that’s not what I do, but I want them to see what I’m doing. My next mini-book that I’m producing is my … I don’t know what I’ll call it. It’s the cosmology book, it’s all the work I’ve done since 2012.

Well, I’ll be first in line for that one.

You’ll get one for sure!

You’ve mentioned the question of dark matter and dark energy, which basically means we don't understand what most of the physical universe is.

Right. You and I are four percent of the universe.

It occurred to me that another thing that we don’t really understand is consciousness. The so-called ‘hard problem of consciousness.’ Do you see cosmology as getting at that question, too? Is that related?

Yeah, I read a lot about that. One of the things I find really interesting is that we — Homo sapiens — are constructed with the elements of stars bursting.

Like Carl Sagan said, we’re ‘stardust.’

We’re stardust, and that’s fascinating to me. If we have consciousness, does a Higgs-Boson have consciousness? Does a quark? That is real interesting, and I’m struggling to make art about that.

There are some in the field of consciousness studies who would say that the current work in quantum physics, issues like non-locality, entanglement, the observer effect, etc., that all this kind of syncs up with ancient religious wisdoms written thousands of years ago. Do you think that’s true?

Yeah, yeah.

What are the implications for art, if that’s true?

Yeah, I think that’s true. The more we learn about the quantum world, the more it explains a lot about our very coarse sense of consciousness. I have a lot of doctor friends, and one is an opthamalogist. I asked him about this, I said, ‘How come we can only see this much of the wavelength? [at this point, Evans held up his hand with his thumb and index finger an inch or so apart] Why did we get so limited?’ And he said that early on, we were probably able to see more, but that tool couldn’t handle all that information. We couldn’t process all that information, so we evolved down to a limit. If that’s true, we are still experiencing all of this wavelength that’s around us, but we’re only picking up a certain amount. And then if all of those things you listed, quantum entanglement and all those things, are true — and they’re becoming more and more true —then there’s bunch of shit going on around us that you and I are not aware of, and it probably has been forever. And probably, early man had a broader sense and was just confused with all that stuff and evolved to tone it down, like turning a radio down. I don’t know if that’s true, but that’s what I think.

That’s a fascinating idea. I wonder if that explains some of the crazy things they wrote and drew.

Yeah! And also, sometimes something happens … maybe it’s a leak of what’s going on that someone’s picked up. I think there’s a lot of stuff going on in our reality that we cannot absorb, and some people have finer sensors that pick it up, and maybe those are the real visionaries, who see other realms.

My idea is that all that could potentially explain at least some of what what we call the ‘paranormal.’ People seeing a ghost, a UFO, or whatever. Pick one. And that at the end of the day, that stuff can actually be explained in a scientific way that we just cannot do now.

Yeah, it could be a wormhole from another universe. The whole idea that we’re the only universe that ever was and ever will be seems absurd to me. I think that ultimate question of theology and every ‘ology’ that is, what was before the Big Bang? Where did matter come from? Did it just appear? Was it energy, was it a vacuum? There’s a theory that the universe keeps creating itself, and that there are parallel ones. All that stuff. I don’t have enough space on my hard drive to make art about anything but that. That’s what I do now.

I really enjoyed reading this and look forward to the second part. I love voices like this; self-taught or just knowing what they want to do. So, please know the content here is great! I do have a technical question--you mentioned AI transcription. Was that fromn audio to text? What did you use? (I'm curious because I'm thinking about a project that involves students who are incarcerated.)